It’s Tough World. Here’s How Parents Can Raise Resilient Kids

When Devon B. was in the fourth grade, the elementary school she attended in Chatham, NJ, noted the wintry conditions about to develop and announced an early dismissal. It was noon and snowflakes had begun to fall, prompting the school to call Devon’s mother. Could she come and pick up her child? It’s OK for Devon to walk, the mother said; home was just half a mile from school. As Devon trudged through the snow, her mother received a handful of calls from concerned parents. Should she be walking alone in this weather?

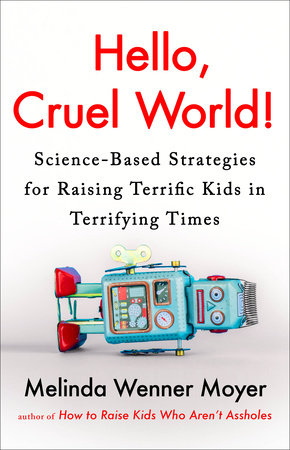

“In situations like this when there is such a small likelihood of danger, it is so much better for a child to be given that independence,” said Melinda Wenner Moyer, a journalist and author of “Hello, Cruel World! Science-Based Strategies for Raising Terrific Kids in Terrifying Times.”

“These are the opportunities we need to give kids to build confidence and resilience,” she added. Inviting children to take healthy risks is just one bit of counsel Moyer offers parents. To prepare kids for an uncertain future, parents should help their offspring learn how to cope, connect with others and cultivate important competencies. Hello, Cruel World! relies on research to explain why children need these skills and offers direction to parents on how best to promote them.

Kids are better able to cope when they learn how to be kind to themselves; self-compassion translates into less anxiety, stress and depression — and more kindness towards others. Resilience, the ability to handle adversity and keep going after failure or disappointment, is also crucial for children. And understanding the need for rest and recovery keeps kids from accepting a permanent state of stress, which erodes well-being. Developing these resources will offer some protection over time against drug abuse and addiction, scourges that afflict those who lack coping skills.

What can parents do? Give kids the vocabulary to discuss their feelings and make clear that being sad or upset is not an abnormality but a part of life, Moyer advises. Back off the performance pressure and normalize failure by sharing your own struggles. Avoid jumping in at every sign of distress, as children interpret such interventions as a sign of their own incompetence. Also, get away from hovering over and tracking your kids, as excessive parental involvement shrinks kids’ motivation and undermines school performance. And resist the false notion that danger lurks at every turn by permitting your child to take reasonable risks—and allowing him to squirm. Along the way, model the behavior you’re promoting: demonstrate self-compassion, use substances responsibly and don’t apologize for taking a break. Moyer offers much more in the way of research-backed advice on boosting children’s coping abilities.

What can parents do? Give kids the vocabulary to discuss their feelings and make clear that being sad or upset is not an abnormality but a part of life, Moyer advises. Back off the performance pressure and normalize failure by sharing your own struggles. Avoid jumping in at every sign of distress, as children interpret such interventions as a sign of their own incompetence. Also, get away from hovering over and tracking your kids, as excessive parental involvement shrinks kids’ motivation and undermines school performance. And resist the false notion that danger lurks at every turn by permitting your child to take reasonable risks—and allowing him to squirm. Along the way, model the behavior you’re promoting: demonstrate self-compassion, use substances responsibly and don’t apologize for taking a break. Moyer offers much more in the way of research-backed advice on boosting children’s coping abilities.

Learning how to connect with others is essential, especially as American society fractures and online activities supplant in-person interactions. Kids need help building compassion and empathy for others and skills in establishing stable relationships, as well as a healthy curiosity.

Mothers and fathers can nurture their kids’ connection skills by showing compassion and concern for others. Building kids’ “cognitive empathy”— understanding another’s emotions without taking on the feeling itself—is more apt to develop when parents talk about feelings, actively listen to their children and avoid scolding them for expressing distasteful views. “Take a breath and bring it up later,” Moyer advises. Invite even very young children to help around the home and be affectionate with daughters and sons. Boys are every bit in need of emotional support as girls, especially given the subtle cues they receive to “man up” at the first sign of anguish. Promote curiosity by asking kids questions and welcoming their queries.

If learning how to cope and connect build well-being, figuring out how to cultivate practical abilities is more of an “outward-turning” talent, one that will help children “engage with the world in a way that’s healthy and productive and constructive,” Moyer told me. Kids need to grasp some basic life skills that may be absent from the school curriculum: financial literacy, media knowledge and social media savvy.

To facilitate these abilities, parents can talk often about budgets, investments and debt. Absent these open discussions, kids will struggle to understand how to manage income and expenses—a growing concern for many young people who are struggling to get by. To support media literacy, mothers and fathers can educate their children about logical fallacies and ask questions about the information itself. What’s missing from the story? Who might benefit? Practicing good media hygiene themselves also helps, as does showing a willingness to tolerate uncertainty. As for social media, parents might allow access to such sites gradually and be mindful of a teenager’s use; active engagement is better than passive use. Try not to panic and be mindful of how often you turn to Instagram and TikTok.

Though her book bursts with guidance, Moyer admits to a certain queasiness about providing parenting advice. “There is no one-size-fits-all approach to raising kids,” she writes, acknowledging that a particular strategy that works for one child may blow up with another. Moyer encourages parents to embrace the approaches that best suit their own family and keep the big picture in mind. When in doubt, Moyer concludes, stick to these three truisms: preparing children is better than protecting them; listening beats lecturing; and comforting is more productive than scolding. “You don’t have to be a perfect parent and it’s good if you’re not,” she told me.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0